NELS

NELS draws domain knowledge from Psychology to enhance the quality of expression of acoustic phenomena.

To enhance the quality of expression of acoustic phenomena, I studied an interdisciplinary solution that combined Machine Learning and Psychology. Psychology has numerous human studies to determine what are the acoustic properties that listeners consider to perceive and describe sounds. Acoustic properties are mainly derived from three areas, Cognition, Psychomechanics and Psychoacoustics. Inspired by the acoustic properties that were successful in listening experiments, we selected categories that could result in Machine Learning models with reliable performance. The new models should expand the expressive capabilities of the three NELS modules, crawling audio from the Web, indexing audio content, and searching for it. This was the first focused study, to the best of our knowledge, on training Machine Learning models based on acoustic properties.

Understanding how humans hear is the primary strategy in designing acoustic intelligence [1]. In the previous project post #5 I mentioned that in order to create knowledge for sounds, we need to define different attributes, relations and interactions between objects. From the perspective of NELS, categorization and search, are fundamentally a question of human interpretation -- how do people refer to acoustic phenomena and what do people find to be meaningfully similar? The way that people refer to sounds is unbounded and signal level similarity can be measured in many ways, which are inherently subjective. Hence, a solution is to investigate human perception of sounds from the perspective of Psychology.

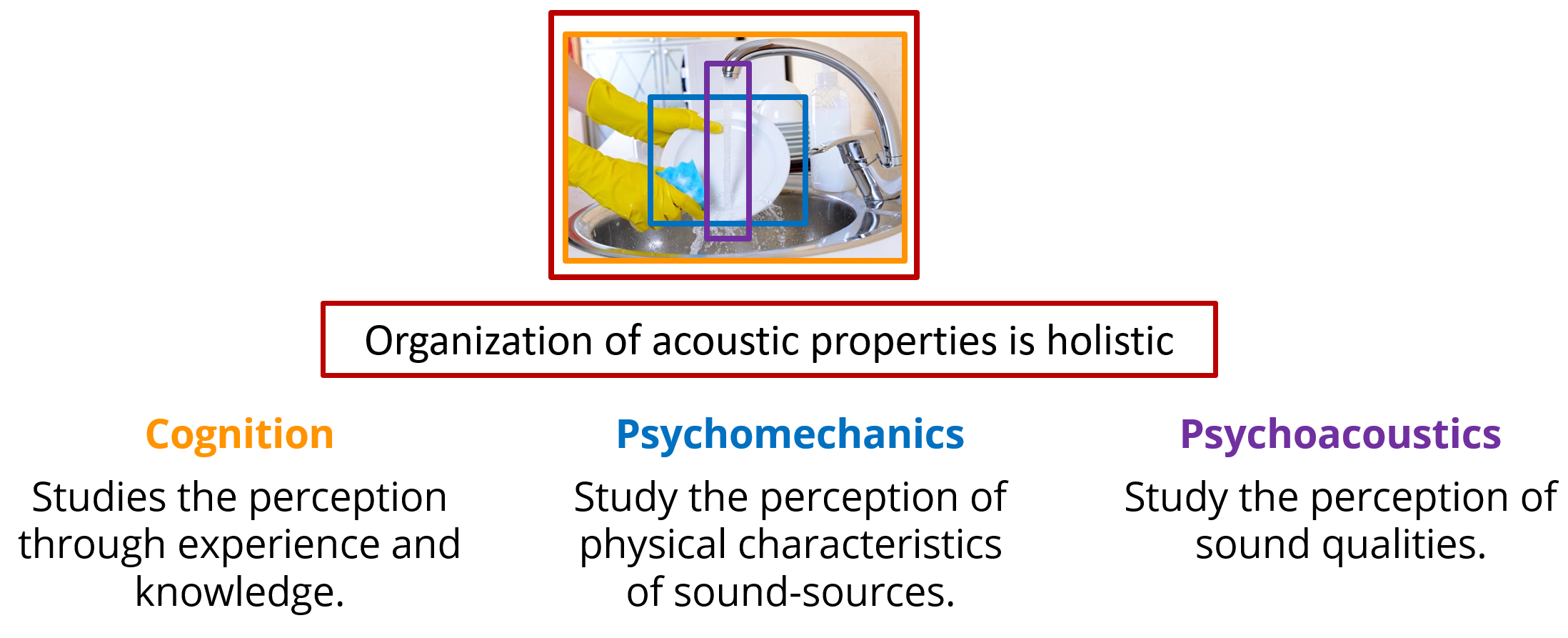

Psychology defines a sound as a complex stimulus that encompasses a vast range of acoustic properties [2,3,4]. For NELS to learn new classes automatically, we need to define what a sound event is. Listeners perceive acoustic properties and combine them in a holistic manner to recognize sounds. Research in Psychology has established that humans are cognitively flexible enough to compare and categorize sounds in multiple ways within three major areas: Cognition, Psychoacoustics, and Psychomechanics.

Cognition studies the perception through experience, knowledge and language [2,4]. Psychological experiments have shown that listeners group everyday sounds based more on individual experiences rather than on shared "common" knowledge. For example, the loudness or quietness of a city's soundscape is not the same for someone in New York City, USA or in Oaxaca, Mexico; the sound of a car engine can be perceived differently by a regular driver than by a car mechanic. Authors in [5] evaluated free-categorization of sounds. When participants were provided with audio clips and were asked to classify sounds without any restrictions, non-expert listeners categorized sounds based on source-objects, but expert listeners could identified sources at different levels of abstraction, for example, "electric" vs. "mechanical sources".

Psychomechanics study the perception of physical characteristics of sound-sources [2]. In the auditory domain, categories are primarily structured based on the sources - object or agents - producing sounds. In fact, authors in [5] shown that non-expert listeners categorize sounds based on source-objects. Nonetheless, Gaver argued that listening to everyday sounds focuses more on the physical aspects producing the sound (e.g. actions, interactions, materials) and what they mean in a given context [8].

Psychoacoustics study the perception of sound qualities [2]. Sounds are associated to a subjective perception and adjectives can elicit a subjective meaning to the listener [5,6,7]. Adjectives referring to emotional factors and spectro-temporal components unfolding over time (e.g. pitch, timbre) are among the most common wording to categorize sounds after constructions using a noun referring to the source and suffixed nouns derived from verbs referring to the action generation - car passing by [2].

To exemplify the three main areas we use the sounds of a dish washing event illustrated in the figure above. Let's say we are in our house, close to the kitchen, but without the visuals of the kitchen. We can recognize the materials involved-- water, glass, metal, and the action of scrubbing (Psychomechanics). We can tell if the sounds were loud or quiet, and if the water was flowing continuously or intermittently (Psychoacoustics). From the context and our experience we can infer the event of someone washing something (Cognition). The listener's perceive, organize, and combine all these acoustic properties in a holistic manner to guess a dish washing event.

We aimed to develop a similar approach for NELS, where we can combine Machine Learning models built on acoustic properties for sound event recognition. The future of systems with Sound Understanding could lie in accounting for different possible relations and similarities between sounds, thus being capable of providing models with different concurrent categorization strategies.

References

- Lyon, Richard F. “Machine hearing: An emerging field [exploratory dsp].” IEEE signal processing magazine 27.5 (2010): 131-139.

- Lemaitre, G., Grimault, N. and Suied, C., 2018. Acoustics and psychoacoustics of sound scenes and events. In Computational Analysis of Sound Scenes and Events (pp. 41-67). Springer, Cham.

- Lemaitre, G. and Heller, L.M., 2013. Evidence for a basic level in a taxonomy of everyday action sounds. Experimental brain research, 226(2), pp.253-264.

- Guastavino, C., 2018. Everyday sound categorization. Computational Analysis of Sound Scenes and Events, pp.183-213.

- Dubois, Danièle. “Categories as acts of meaning: The case of categories in olfaction and audition.” Cognitive science quarterly 1, no. 1 (2000): 35-68.

- Frühholz, S., Trost, W. and Kotz, S.A., 2016. The sound of emotions—Towards a unifying neural network perspective of affective sound processing. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 68, pp.96-110.

- Ntalampiras, S., 2017. A transfer learning framework for predicting the emotional content of generalized sound events. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 141(3), pp.1694-1701.

- Gaver, W.W., 1993. What in the world do we hear?: An ecological approach to auditory event perception. Ecological psychology, 5(1), pp.1-29.

Date: Published on June 2021 from work done during my PhD between 2015-2020.