NELS

NELS limitations categorizing and describing sounds.

Building Machine Learning models for the NELS modules exposed that current categorization limits performance and quality of expression of acoustic phenomena. We summarized the limitations in three main aspects. First, categorization of sounds is highly subjective and can be lexico-acoustically inconsistent, affecting crawling quality and performance of Machine Learning models. Second, how we name sounds in search and retrieval is limited to one or two words, but we should enable elaborated descriptions. Third, to learn knowledge about sounds we need to define names and relationships for acoustic phenomena beyond sound-sources (nouns). From the perspective of NELS, quality of expression is fundamentally a question of human interpretation.

Categories based on source-objects often assume that they can produce only one prototypical sound, limiting recognition performance of Machine Learning models. For example, think about the most typical sound produced by a helicopter and an airplane. Look at the helicopter and airplane images above, what is the typical sound that each of them would produce? Each airplane has a different engine, how would you categorize each sound? Would you group both sounds under the same category, or would you group the sound associated to the three images into the same category, what would be the name? NELS audio indexing evidenced this issue with one of its classifiers trained in a well-studied sound event dataset called ESC-50 (and AudioSet), where several classes are defined by their sound-source. The author of the dataset carried on human classification experiments and showed that "airplane" was the lowest performing category with 60% accuracy, highly confused with "helicopter". The dataset contains several recordings with an airplane that has a rotating engine, which is acoustically similar to the rotating engine of the helicopter. Unsurprisingly, Sound Event Recognition systems exhibit the same confusion thus, can we train a model to achieve 100% accuracy in ESC-50?

To learn knowledge about sounds we need to define recognizable names, attributes, relations, and interactions that produce acoustic phenomena. For example, if we have a sponge, a plate and a faucet, what sound(s) do each of them produce in isolation and what sound(s) do they produce in combination? NELS should eventually be able to have and grow a knowledge base of sounds, something that until this day is not available, but how to start? We could use language to relate elements that compose sound events (e.g., WordNet), or autoregressive models to generate acoustic descriptions of sound events (e.g., GPT3), however, language-based model seem to lack audio understanding and not always associate words that produce sounds (e.g. sitting in a chair vs pulling a chair, looking at a tree vs tree falling down). The knowledge we define and how we use it will impact the performance of Machine Learning models.

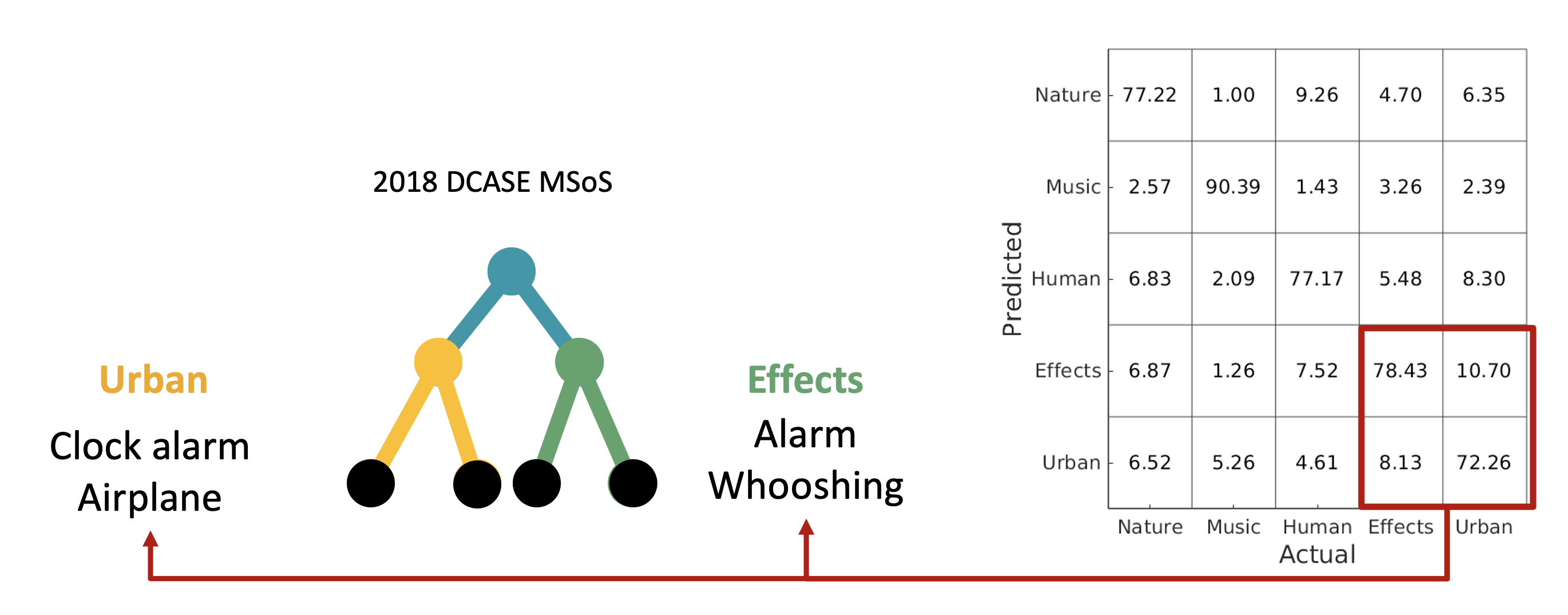

Organization of categories based on semantics is highly subjective and have many alternatives, affecting the performance of Machine Learning algorithms. In the 2018 DCASE Making Sense of Sound Challenge, the goal was to perform classification of coarse-level categories using audio from fine-level categories. The figure above shows on the right the confusion matrix of the accumulated coarse-level classification scores of the 12 participating teams. One big confusion happened between the coarse-level classes "effects" and "urban". Their corresponding fine-level categories shared the semantic meaning, but did not always shared acoustic similarity. In the left of the figure we show "urban" and "effects" with the corresponding fine-level classes "clock alarm" and "alarm", or "clock tick" and "click", or "airplane" and "whooshing". Each pair has similar acoustics even though they were on different coarse classes. Instead, we could have grouped together both alarms, and airplane with whooshing.

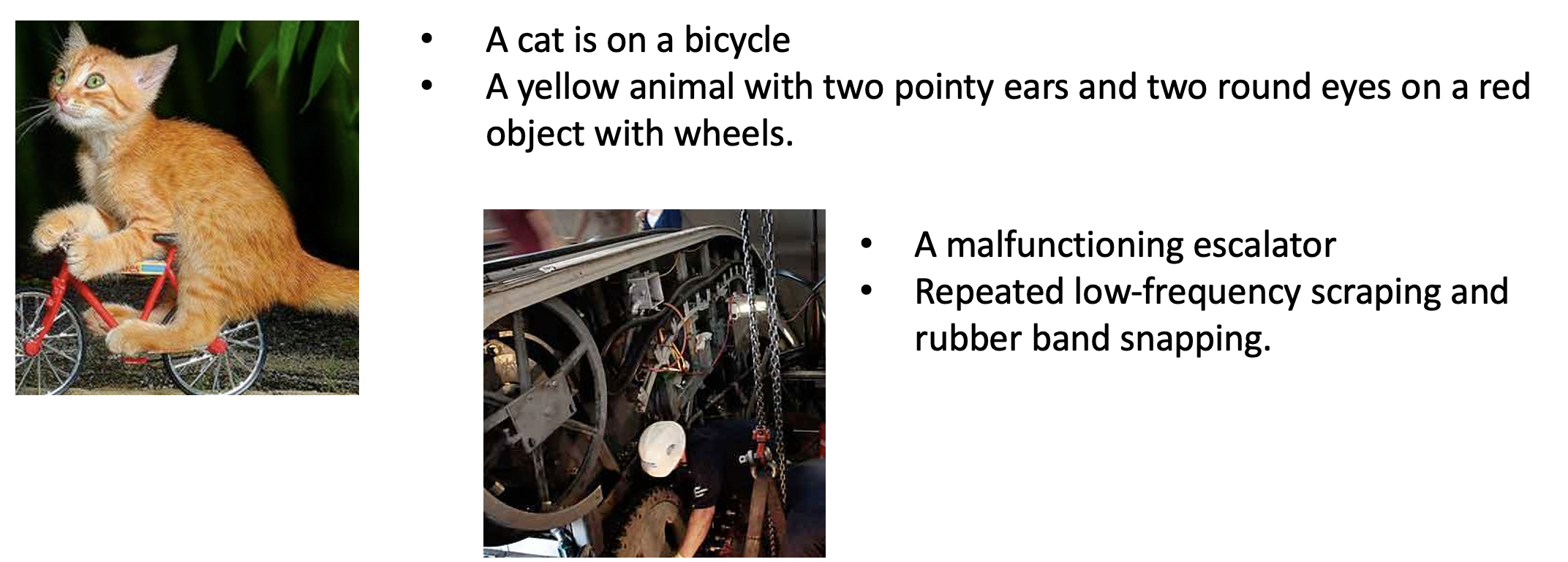

Search of acoustic phenomena was limited to one or two words, but we often require multiple terms to describe acoustic phenomena. We exemplify it in the figure above. To visually identify the first image, which of the two descriptions is sufficient? Either, a cat is on a bicycle, or a yellow animal with two pointy ears and two round eyes on a red object with wheels. The former is probably enough. To acoustically identify the depicted event in the second image, which of the two descriptions is sufficient? Either a malfunctioning escalator, or a repeated low-frequency scraping and rubber band snapping. The latter provides us with an acoustic definition that a repairman can translate into urgent maintenance.

Lemaitre et al [1] mentioned that users of automatic systems for recognition and retrieval, usually complain about not experiencing proper or sufficient categories. An explanation is because there are many possible categorization processes, and the most appropriate categorization depends on the sound, the user, and the context, so often we need multiple terms to elaborate a description. Descriptions are essential for search and retrieval of acoustic phenomena, especially when the source could not be identified [2]. The future of such systems may lie in accounting for different possible similarities between the sounds, thus being capable of providing different concurrent categorization strategies. Therefore, we need to be able to train Machine Learning models not only on classes defined by source-objects and scenes, but also based on other category types such as sequences, actions, materials, shapes, sizes, cities, attributes and sentiments.

Even if we increase the category types, we still have limited lexicalized terms in language to describe acoustic phenomena. This is a particular instance of the Sapir Whorf hypothesis, where the structure of a language determines a listener's perception and expressiveness of a perceived phenomena. For example, the sound of water is one of the most distinguishable sounds, but how to describe it without using the word water? Despite limitations in language to describe acoustic phenomena, we should still be able to automatically describe acoustic content of a signal at least as good as humans do.

References

- Lemaitre, Guillaume, Olivier Houix, Nicolas Misdariis, and Patrick Susini. “Listener expertise and sound identification influence the categorization of environmental sounds.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 16, no. 1 (2010): 16.

- VanDerveer, Nancy Jean. Ecological acoustics: Human perception of environmental sounds. Cornell University, 1979.

Date: Published on May 2021 from work done during my PhD between 2015-2020.