NELS

NELS improves hearing with unlabeled audio.

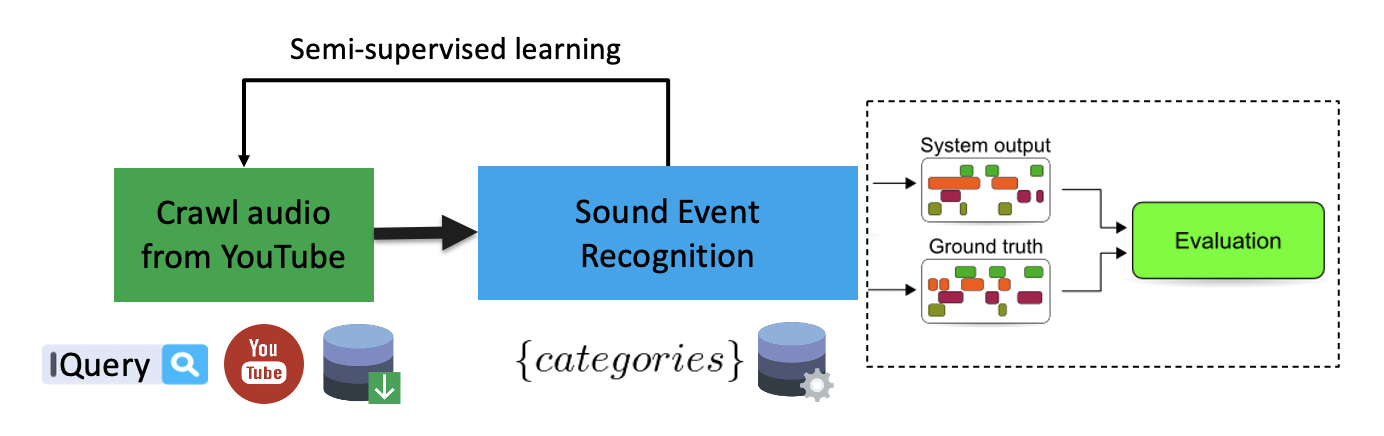

NELS can take advantage of the continuously crawled unlabeled Web audio to improve its recognition models using semi-supervised learning as described in our paper [1]. Semi-supervised learning can be summarized in the following steps. First, a sound recognition system is trained using audio with labeled sound events and then evaluated in a test set. The system is used to recognize and label sounds on an often large unlabeled set. Using a selection of the newly labeled audio, the system is re-trained, then evaluated again with the test set, often with performance improvement. The process is repeated until there is no improvement. One question to conisder is "Should we re-train sound recognition systems based on acoustic similarity only or based on both acoustic and semantic similarity?"

Although there were a few papers on this topic, to the best of our knowledge, our study was the first to use audio from Web videos and with one order of magnitude more recordings. For our experiments we used a standard sound event dataset and unlabeled audio crawled from YouTube. The Urban Sounds dataset has 8 thousand recordings from 10 classes: "air conditioner", "car horn", "children playing", "dog barking", and "street music", "gunshot", "drilling", "engine idling", "siren", "jackhammer". The unlabeled audio were crawled YouTube videos corresponding to the 10 classes. The query for crawling was a combination of keywords: "sound event label" + "sound" (e.g. "air conditioner sound"). We segmented the crawled audio into 200,000 segments of 3.5 sec, similar to Urban Sounds. The crawled audio often, but not always, had the target sound event, the sound duration was variable, and the sound may be overlapping with background noise, or other sounds.

We evaluated two different Machine Learning recognition systems, and evaluated three methods to select unlabeled audio for re-training. Audio was characterized with Bag-of-Audio-Words features built over Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients. The recognition systems were binary classifiers, one per class, based on Support Vector Machines and Neural Networks. The three methods to select candidates were systems' output probability, systems' output precision, and clarity index. The classifier's output was a probability that can be interpreted as a confidence value. High precision means that the classifier recognizes relevant instances of the class. Clarity Index identifies samples that are close to the decision boundary of the classifier, or in other words, the hardest sounds examples to learn.

We evaluated Sound Event Recognition using average precision. The baseline performance was computed using our classifiers on the labeled testing set without any re-training. At each iteration, we ran the systems on the 200,000 unlabeled segments to select candidates for re-training for all the 10 classes and computed average precision. The process was repeated in an iterative manner until the performance stop improving. We carried on three independent re-training experiments, one for each candidate selection method.

The overall performance after re-training did not improve dramatically, we achieved 1.4% overall improvement after five iterations using Clarity Index. One interesting insight is the notion of classes in audio can be inconsistent, thus any semi-supervised method may have a ceiling because an audio clip can be categorized into multiple acoustically similar, but semantically different categories, confounding the training of the system. For example, "gunshot" was often re-trained with audio of objects banging. Another example was "Clapping", which mostly included audio of crowd clapping. The performance of the "clapping" recognizer improved using crawled audio. However, few of the crawled recordings labeled as "clapping" were used for retraining, after a close inspection, these recordings had the sound of a single clap. Instead, the crawled audio that was used for retraining corresponded to "rain (falling)", which was acoustically similar. The problem is that we do not know a priori which classes will have this issue. Hence, should we re-train systems based on acoustic similarity only or based on both acoustic and semantic similarity?

References

- Elizalde, Benjamin, Ankit Shah, Siddharth Dalmia, Min Hun Lee, Rohan Badlani, Anurag Kumar, Bhiksha Raj, and Ian Lane. “An approach for self-training audio event detectors using web data.” In 2017 25th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO). IEEE, 2017.

Date: Published on Mar 2021 from work done during my PhD between 2015-2020.